So, what is the day in the life of a medical student like?

That depends on the school and the year one is asking about. For instance, Baylor 1979-1983, was a traditional 4 year curriculum with 2 years of classroom and lab work then 2 years of supervised, clinical, hands on patient care. Right across the street was the University of Texas Medical School-Houston and the structure was different with them doing a mix of classroom and clinical starting in the first year.

Now, Baylor is doing the same thing as UT did back when. From the Baylor web site, “The traditional model with its abrupt transition from classroom focus on basic sciences to clinical rotations is replaced by longitudinal integration. Early introduction to seeing patients provides meaning and context as you gain the foundational knowledge required to practice medicine.”1

My personal experiences would be mostly archaic, so let me approach the question as I think it would apply to today’s new students.

Time management?

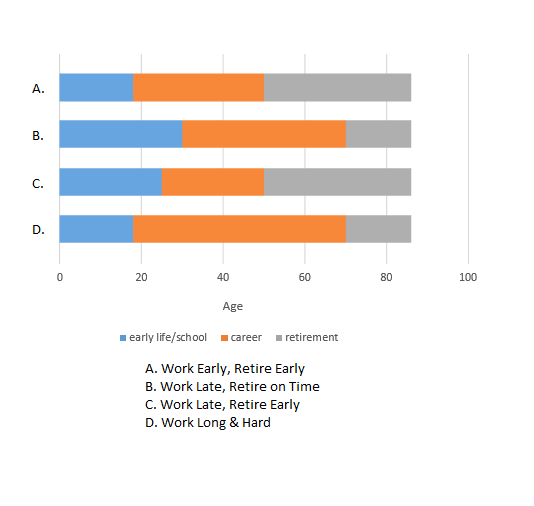

There’s an oxymoron for you, if there ever was one. It is really an issue of organization of time usage. The major difference between University life and Medical School life is the pressure one feels to assimilate the large amount of information. The holidays are the same and weekends are off unless you are on a clinical rotation. After my first year in practice, I was amazed at how much time is free time in Universities and Medical school. You’ll wont see that much free time again, until you retire or die.

As soon as you get your schedule for the semester or year or whatever, start planning how you will organize your time. It is always helpful if you find somebody that has done the same rotation and query them as to how it works. How time is organized will vary depending on each individuals sleep and study habits. Regardless if you are a day person or night person, one who studies constantly or a last minute crammer, you need to plan out your use of time. If you are married or are in a relationship, share the plan. Calendars, electronic or paper, are a must. This is a good time to put your OCD to good use.

Food

Resist the urge to eat when you are tired, thinking that it will re-energize you. It won’t. It will just make you even more tired. And you will not be getting as much exercise as you might need. And you gain weight. Causing the whole process to spiral down.

One thing students and residents become expert at is finding noon conferences that serve food. Make the effort to identify these. If you are not required to be elsewhere, attend one. Larger medical centers will probably have several to choose from Monday-Friday. Usually, at the end there will be a few items left over and if you are on call that night, hey you now have scored 2 free meals.

Family, spouse, pets

Family, spouse, non-married relationships, significant other, boyfriend, girlfriend or whatever you call them, if you live with them you owe them respect. I strongly recommend a face to face discussion about expectations before you start on this journey.

There will be times when the medical student has to work late, can’t get to a phone to call, changes plans at the spur of the moment, hits the wall of sleep deprivation, stresses or feels over whelmed with duties. There will be times the other one, the non-medical-student, becomes frustrated with the seeming abandonment, the loss of attention or feels over whelmed with duties at home from financial obligations, the burden of children without the help of the medical student, or whatever. The various scenarios are infinite, but if many of them can be acknowledged ahead of time, it makes handling the unforeseen easier. There has to be give and take on both sides and both have to be willing to sacrifice something for the other while accepting the sacrifice of the other with grace. When talking to each other, use common respect. Use please, thank you and other forms of polite discourse regardless of how tired or stressed you are. Don’t raise your voice, ever. Don’t roll your eyes, grit your teeth, sigh heavily or show any subtle body language to say what you shouldn’t.

Avoid the trap of language. The medical student is going to learn another language with idioms unfamiliar to the non-medical-student and it is sometimes consciously tempting and sometimes unconsciously spontaneous to use this new language. The language should remain the same as it was before medical school. In other words, don’t use fancy, high highfalutin medical terminology in sincere conversations with your non-medical-student mate.

Arrangements to care for pets in case of unforeseen delays or in prolonged absences should be made. A cat or dog sitter that the animal is familiar with and likes will go a long way to avoid destructive behavior these companions can come up with.

Navigational skills

Especially at older and larger centers, navigation skills are important. Or recognizing that it is a personal deficiency and learning who among you has those skills and sticking close to them. Older centers started, probably, as a single building and as needs arose, were added on to. To do that, architects were hired and plans drawn up and implemented. I don’t mean to be insulting, but one of the chief requirements to becoming a medical facility architect is learning how to connect medical buildings in the most M.C. Escher fashion.2

Just get along

I guarantee that at some time in your training, you will come across someone you don’t like or that doesn’t like you. Develop the skill of not letting this interfere with your work product. Cat fights, baiting, inter-team rivals or just all out brawls are not going to help your patients get better or help your learning process. It may even be the patient that has issues with you. Be stoic. Don’t let your emotions show. Address the problem or issue in an honest but gentle manner without resorting to hyperbole, baiting, unprofessional language or demeanor or attempts at domination. After all, it is your job that’s at risk. You’ve worked hard to get here, work hard to stay.

Nerves

The best way to calm nerves is confidence. Public speaking, presentations on rounds, interviewing a patient, etc. Having the confidence that you are well prepared for the topic at hand and having experience of numerous prior contacts in this situation is a cure for the jitters. Some people use drugs, such as propanolol for example. But if this works, it doesn’t work if the encounter is spontaneous and immediate and you haven’t had the opportunity to take the drug. I prefer and recommend gaining confidence by study and repeat exposure. In other posts, I have advocated group studying. See one, do one, teach one. The best avenue to learning something new. In a study group, a given topic can be assigned to a member to research and give a presentation to the group. It’s a great complement to traditional studying techniques.

Scut work

Scut work could include drawing blood for lab testing, starting IVs, retrieving report results, communicating with other teams, nurses or staff. Before computers, students often would be expected to find and retrieve the paper medical charts of the patients on the service. Believe me, computers have astronomically improved and eased this task. But, scut work is still learning and it’s paying your dues for the education you are getting from other team members.

Sleep deprivation

Modern training regulations limit the amount students and residents can be made to work.3 That is unfortunate. The reason I say this is because, until you have been challenged, you don’t know your limits. Many times in my career, I have had to work for many more hours than the current training guidelines define as reasonable. If I didn’t work those hours, patients would not have been able to get medical care because there wasn’t anybody else. It is part of the package that you are getting in choosing medicine as a career.

Drugs

Don’t. Various forms of speed, amphetamines including Adderall and the like, are a trap. There was a saying in the 60’s, when drugs and free love were so prevalent, “Speed Kills.” Believe it. One might get by for awhile, even some might get by completely, but for most, you will be adversely affected. Besides, it’s illegal. Even having a physician prescription can be illegal if the diagnosis was obtained nefariously.

Your Uncle Dave,

Weary

1. (https://www.bcm.edu/education/schools/medical-school/md-program/curriculum/foundational-sciences-curriculum)

2. (https://moa.byu.edu/m-c-eschers-relativity/)

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_resident_work_hours